This blog post is Part 4 of our Mini-Series On Cancellation Of Removal for non-lawful permanent residents, an important component of our deportation defense services.

The limits of prosecutorial discretion have been revealed.

According to the New York Times, only 16% of immigrants facing deportation hearings at immigration court are being granted temporary refuge from immediate prosecution.

The suspended hearings can be reopened at any time.

Deportation proceedings in one year, two years, three years can begin anew.

In addition, Chris Crane, ICE union president, has issued orders to his 7,000 membership They are not be allowed to participate in the administration’s training classes on the new prosecutorial discretion guidelines.

Once again, the promise of a humanitarian solution for undocumented immigrants with deep family and community ties, and no criminal history, remains unfulfilled.

For most of these individuals, it’s back to immigration court.

And the deportation hardship quagmire.

The Cancellation Of Removal Hardship Quagmire

Under Cancellation of Removal For Non-Lawful Permanent Residents, even when immigrants are able to demonstrate a wide variety of hardship factors, they are often denied relief from deportation.

They are told the hardship to their U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident family members is not severe enough.

This means, in the judge’s view, their qualifying relatives’ hardship does not rise to the level of an “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship”.

In several instances, however, the severity of their family’s situation is sufficient to warrant a finding of “extreme hardship”.

So what’s the difference between an “extreme hardship” and an “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship”?

Good question.

Six Degrees Of Hardship

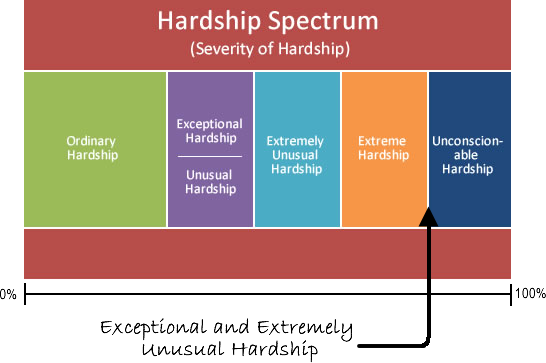

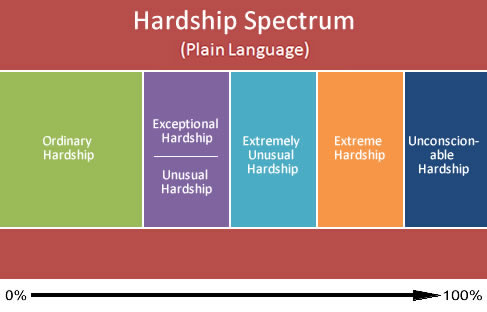

Ordinary, exceptional, unusual, extreme, and unconscionable.

From least to most severe, these are the various degrees of hardship severity identified by immigration courts.

According to well-respected dictionaries like Webster’s, Oxford, and Cambridge, a comparative list of their commonly accepted meanings follow:

- Ordinary – plain, undistinguished, customary, usual, normal, commonplace, unexceptional, no special quality

- Exceptional – unusual, extraordinary, irregular, peculiar, rare, strange, unnatural, anomalous, abnormal

- Unusual – uncommon, extraordinary, exceptional, rare, strange, remarkable, singular, curious, queer, odd

- Extreme – utmost, greatest, rarest, highest, outermost, endmost, uttermost, farthest, furthest, remotest, ultimate

- Unconscionable – immoral, barbarous, preposterous, uncivilized, unethical, excessive, wicked, conscienceless, unscrupulous

Based on this review, a plain language spectrum of hardship severity can be discerned.

As this spectrum shows, the only hardship more severe than an “extreme hardship” is an “unconscionable hardship.”

That’s a crucial point to understand.

Unfortunately, immigration appellate courts have failed to grasp its implication.

Consider:

Where does an “extremely unusual hardship,” a sixth term used by immigration courts, fit in?

Under a plain language approach, there is only one plausible meaning.

An “extremely unusual hardship” is more severe than an “unusual hardship”. But it is less severe than an “extreme hardship”.

Exceptional And Extremely Unusual Hardship

In 1952, as the history of immigration hardship shows, the fictitious concept of “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” was added to the lexicon of deportation law.

Congress was open about its’ meaning:

“To justify the suspension of deportation the hardship must not only be unusual but must be exceptionally and extremely unusual. The bill accordingly establishes a policy that the administrative remedy should be available only in the very limited category of cases in which the deportation of the alien would be unconscionable.”

In short, according to Congress, “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” is just another term for “unconscionable hardship.”

Exceptional and Extremely Unusual Hardship = Unconscionable Hardship

Really?

Twisting The Parameters Of Hardship

Starting in 1962, courts switched to a two-track system of judicial review and employed an “extreme hardship” standard to determine which undocumented immigrants facing deportation on less serious charges deserved to remain in the U.S.

In 1996, a political backlash against immigrants struck. Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA).

This led to the birth of Cancellation of Removal and the re-imposition of the exceptional and extremely unusual hardship standard for all undocumented immigrants, not simply those with serious criminal offenses.

Immigration judges were quick to embrace the notion of a stricter hardship standard laid out by Cancellation of Removal.

As an immigration appeals lawyer, I read a lot of court hearing transcripts.

After losing their cases at immigration court, clients visit my office seeking to challenge the trial judge’s decision. Studying the case history is one of my first duties.

Thus, I was not surprised when, barely a few months after IIRAIRA’s implementation, I read my first transcript involving a denial of deportation relief under Cancellation of Removal.

The judge emphasized “the level of hardship has been heightened deliberately by Congress who perceived that the Immigration Court and Board of Immigration Appeals was weakening the extreme hardship of the former suspension remedy.”

In their haste to embrace Cancellation of Removal, judges turned a deaf ear to what a hardship standard stricter than an extreme hardship really means.

Instead, they promoted a myth that the legal meaning of “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” had changed under IRRAIRA.

They refused to acknowledge, despite over 40 years of case law, the IIRAIRA hardship standard was the same as “unconscionable hardship.”

To date, more than two decades of disastrous cancellation of removal decisions later, immigration courts still cling to this fantasy.

The BIA Cancellation Of Removal Hardship Fallacy

Soon after the implementation of Cancellation of Removal, the rollback of humanitarian leniency became a major source of debate within immigration circles.

The BIA, in Matter of Monreal, sought to moot the discussion of unsconscionability.

However, rather than clarify the distinction between the two hardship standards, the BIA confused the issue even further:

“We are not persuaded . . . that a respondent’s deportation be “unconscionable” in its effects on a qualifying relative before a respondent can be found eligible for cancellation of removal . . . [T]here is nothing in the legislative history of the current cancellation statute to suggest that such an extreme (i.e., unconscionable) standard should be applied.”

The BIA explanation not only directly equated extreme hardship with an unconscionable hardship, but also asserted exceptional and extremely unusual hardship is less severe than an extreme (i.e., unconscionable) hardship.

At the same time, in direct contradiction, the Board concluded that although Monreal may have qualified for deportation relief under extreme hardship, his case did not rise to the higher level of an exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.

In other words, is an extreme hardship more severe than an exceptional and extremely and unusual hardship? Or vice-versa?

The Monreal decision speaks out of both ends of its mouth at once.

Such contortions obfuscate the truth and mislead the public.

Further, as a Riverside immigration lawyer, I am disappointed clarification from federal courts has not been forthcoming.

For instance, in a timid response, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals also side-stepped the issue that the new hardship standard was equal to an unconscionable hardship:

“If the BIA interpreted “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to mean that no hardship showing would ever be sufficient, its interpretation would be so divorced from Congress’s mandate as to violate the Constitution.”

Confusion abounds.

IIRAIRA’s effort to impose a more restrictive standard of hardship, to paraphrase Harvard law professor Roberto Unger, has created “a prison house of paradox whose rooms do not connect and whose passageways tie nowhere.”

Hardship Is Not Just A Grammatical Debate

The unfairness of the current hardship standard is not simply a grammatical dispute.

Even when immigrants demonstrate a wide variety of hardship factors, they are often unable to surmount the disingenuous barrier to relief from deportation imposed by judges under the guise of “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.”

To summarize, here’s how it works.

The Board has placed the fictitious category of “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” between “extreme hardship” and “unconscionable hardship”.

Utilizing this fictitious category, judges are allowed to impose a hardship standard more severe than an extreme hardship on the pretense of legal rationality.

Yet, as Congress realized long ago, there is only one hardship standard higher than an extreme hardship. It’s an unconscionable hardship.

This means, in other words, the Board has sanctioned the deportation of countless immigrants – many with meritorious claims – based on unconscionable hardship calculations.

And an unconscionable standard, in any area of law, is not considered a rational standard.

After all, as noted above, an unconscionable hardship is defined as an “immoral, barbarous, preposterous, uncivilized, unethical, excessive, wicked, conscienceless, unscrupulous” hardship.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics

You can find the other blog posts in our four-part Mini Series On Cancellation of Removal for non-lawful permanent residents here: