“You’re not like them.”

What successful ethnic minority person in the United States has not heard that sentiment?

Perhaps it was a statement over a glass of wine at a company Christmas party. At lunch with co-workers. Or at a school function for their children.

As a Riverside immigration attorney, I’ve even heard similar expressions inside judicial chambers and lawyer meetings.

It’s often expressed in the third person.

“But Julio is not like other Salvadorans.”

This perspective has two major flaws.

First, “the them”, “the others,” are a social fiction.

On a macro level, the fiction is fueled by a xenophobic propaganda machine – a machine that intentionally distorts Americans towards distrust and hatred of immigrant newcomers to our nation.

Second, I am my ethnic brethren.

On a micro level, I am “them.” Those who artificially distinguish me from cultural brethren on the basis of my social status are woefully misguided. Any good I achieve in this life is part and parcel of my cultural genes, traditions, and upbringing.

It’s time for the American public to hear the other side, to learn the real immigrant story.

It’s time to acquaint the ever-so-blind public with Julio – and all the other immigrants who are, in fact, like Julio.

In this post, you’ll meet one such person.

The Disruption Of Civil War

Born in El Salvador, Ana Martinez was raised in a comfortable environment.

Although she did not know her father, her mother’s family members held respectable positions in the Salvadorian government.

Her grandfather had been a colonel in the military.

A former Ms. Universe contestant, pianist, and opera singer, her mother worked for the Ministry of Education, raising Ana and her two brothers as a single parent.

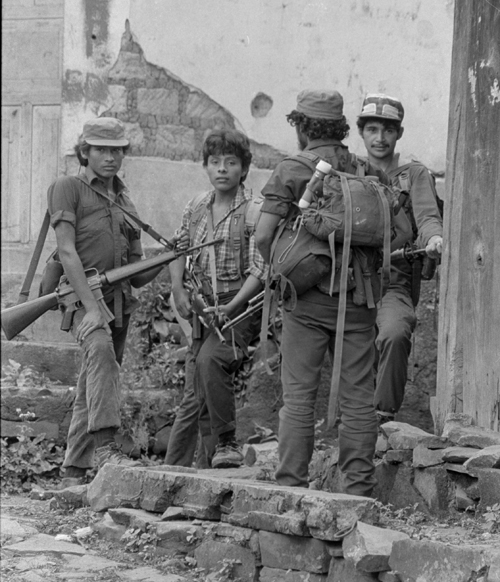

However, a civil war erupted. This tore the country apart and placed her family in jeopardy.

Shortly after Ana’s two older brothers, one majoring in engineering and the other in arts, enrolled in college, they began participating in student protest activities. Within a few months, the civil war escalated.

Ana’s brothers were approached by guerrilla leaders. They feared retaliation if they did not join the movement to overthrow the government.

They did not support current government policies. Yet, they did not think the guerrillas approach was a path for their country to endorse.

To protect her sons, Ana’s mother sold the family home and used the money to send them to live with relatives in the United States.

Within the next year, the conditions in El Salvador worsened. The civil war grew more violent. Murders and massacres spread. Ana’s mother knew she and Ana might become a target for the guerrillas. Painfully, she decided they, too, had to move.

On the morning of Ana’s ninth birthday, Ana and her mother left to join her brothers. Ana’s entire wardrobe consisted of three dresses.

Like her mother, Ana couldn’t speak, read, or write English.

The journey to America did nothing to reassure Ana that things would be okay, or that leaving home would improve their lives.

She and her mother traveled through El Salvador, Guatemala, and Mexico – by bus, car, train, and foot. They went without food and comfortable sleep for long hours. People they met along the way were often rude and mean-spirited.

After several weeks, they reached the Rio Grande. They entered the United States in mid-September of 1981 and relocated in Los Angeles, California.

An Unfriendly Welcome

Ana was miserable and upset after the move. She had not wanted to leave her country. In El Salvador, she had left a nice home, close friends, and nine-year old fun.

She did not like her new school. She could not communicate in English.

Her mother rented a small room as sub-tenants in the Korea Town area. Her mother, once a respected government employee, found work as a housekeeper, earning far less than minimum wage.

Her brothers, having been in the U.S. a year longer, took on the burden of providing for their mother and little sister.

High achieving college students at home, one brother went to work as a janitor and the other took a job in a textile factory while they went to school at night to learn English. Together they earned enough to pay for a studio apartment so the four of them could live together again.

Ana was transferred to a school in Santa Monica, which, in the early 1980s, was not a culturally diverse area. She recalls how elementary classmates called her a “wetback” and other derogatory names. Even though she was from El Salvador, they taunted her, “Go back to Mexico. We don’t want you here.”

A Little Help Goes A Long Way

Soon afterwards, Ana and her family caught some lucky breaks.

First, Ana found a new friend, a girl from Puerto Rico who spoke both fluent Spanish and English. With her friend’s help, Ana began learning English. By the sixth grade, Ana was a “C” student.

Second, a new immigration program called legalization was approved by the Reagan Administration. Originally, the family’s only option to earn green cards seemed to be asylum. The new law, however, enabled Ana’s family to become lawful permanent residents and, over time, naturalized U.S. citizens.

Having mastered English, her older brothers resumed their college studies and became successful professionals.

One graduated with a degree in computer technology. He continues to work in this field today. The other is currently the Chief Executive Officer for an Assisted Living Facility in Studio City.

Ana also pursued higher education.

She graduated from Pomona High School in 1990. She was accepted to San Diego State University but the pace was too fast for her. She left SDSU and re-enrolled at San Bernardino Valley Junior College. After earning an Associate Degree of Science in 1996, she passed the State Certification exam and became a Registered Nurse.

In 1999 she resumed her college studies, enrolling at Holy Names University in Oakland, California. She graduated in 2001 with a B.S. degree in Nursing.

After graduation, she worked a few years at the Loma Linda Medical Center before taking a position at Kaiser Permanente, where she currently works in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit.

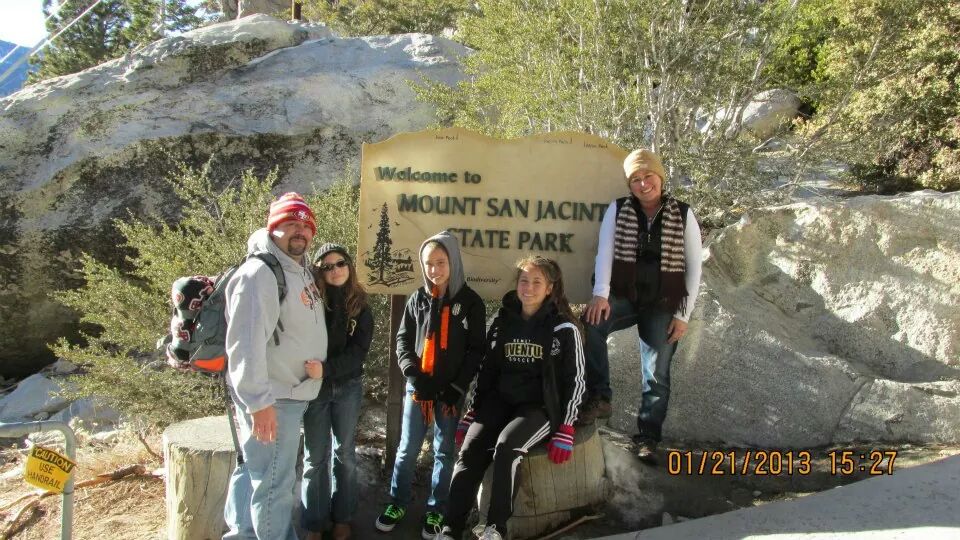

At SDSU, Ana met Jose Martinez, her current husband, in 1994. After their marriage, Jose attended graduate school at California Baptist University. He now teaches at San Jacinto High School. They now have three daughters, two of whom are attending college.

Looking Forward, Looking Back

Besides working full-time, Ana has dedicated many hours to her community. At one point, she volunteered 20-30 hours week, serving as the PTO President at her oldest daughter’s middle school and PTA historian at her younger children’s elementary school. She served on various boards and committees for the local school district.

Ana works closely with Hispanic parents, many of them first generation immigrants like herself. She understands the move here can be overwhelming. In particular, she feels a special mission to work with students who struggle in school, just as she did many years ago.

“Too many young Hispanics,” she notes, “do not see school as important. They just want to get through school, and view college as a waste of time. They don’t want to learn English and just want to go to work, even if it is a low wage position.”

Ana no longer misses El Salvador. Her memories are blurred. She does not follow news about her homeland – except for a brief period when Armando Calderon, her mother’s cousin, was President during the mid-1990s.

She does not know what happened to her childhood Salvadorian friends, and she has not contact with distant relatives who still live in El Salvador.

Ana wants to go back someday for “closure” and to show her children where she and her family lived.

Despite earning a college degree and working as a professional for over a decade, Ana still experiences discrimination. When she enters a hospital room, patients sometimes ask her, “Are you here to take out the trash?”

Co-workers ask her why other immigrants aren’t like her. She hears their complaints, “They’re a bunch of free-loaders living on welfare with too many kids.”

She knows such comments are unfair criticism made by people who do not understand the immigrant’s journey to America.

Hostility towards immigrants, she feels, has increased over the past 20 years – and under the current administration, it has become commonplace to downgrade immigrants.

Normally, Ana doesn’t waste time responding. In her view, people will always have biases and prejudices.

Instead, she focuses on her good fortune. “In America, you can make a difference. You can live a better life. With a little sacrifice and hard work, you can achieve almost anything.”

In fact, with a little sacrifice and hard work, we’ll ultimately win the hearts and minds of the American public – as they learn that immigrants are crucial to our national identity.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics

(Note: An earlier version of this article was posted in Batara On Immigration: Personal, Passionate, And Provocative.)