A friend in need is a friend indeed. But it’s what happens after the need subsides that the real quality of friendship is determined.

Take the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program (FWVP) implemented by the Obama Administration on June 8, 2016.

The new program, noted UCSIS Director Leon Rodriguez, “honors the thousands of Filipinos who bravely enlisted to fight for the United States during World War II.”

The commentary both overstated and understated the reality.

The Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program: Too Little, Too Late

On the one hand, FWVP is a tribute to Filipinos who played a role in America’s World War II victory. On the other, after a 70 year delay, during which period most Filipino World War II veterans have passed away, the window of opportunity for many deserving Filipino families no longer exists.

The policy is the latest in a long series of piecemeal measures to restores promises made by the U.S. government in 1941, in the early days of conflict with Japan, but revoked soon after victory in 1946.

World War II Promises Of

Citizenship And Benefits

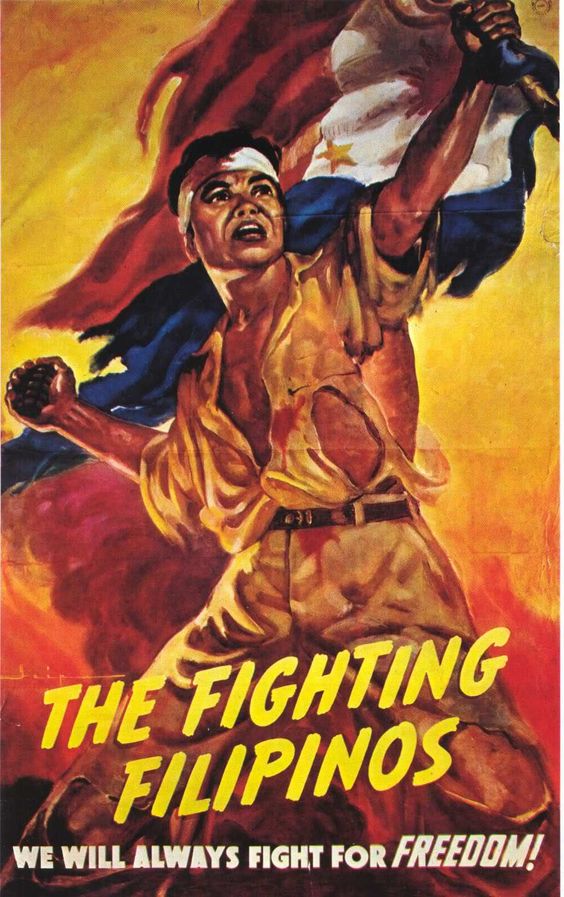

In early 1941, suspecting war with Japan was imminent, the U.S. began to recruit Filipinos to build a military defense force in the South Pacific. At the time, the Philippines was a U.S. territory and Filipinos were considered U.S. nationals.

In exchange for their service, Filipino soldiers were promised American citizenship, full pay, and veterans benefits.

More than 260,000 Filipinos signed up. More than half died in combat.

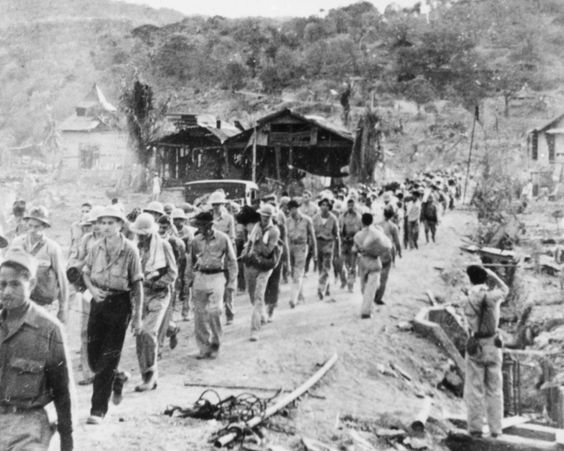

Due to inadequate training time and equipment, many Filipino units suffered catastrophic defeats. In fact, one of the worst American defeats, anywhere during World War II, took place in the Bataan peninsula, located south of Luzon, in May 1942.

After the Bataan surrender, the captured forces were forced to march 62 miles from Mariveles, Bataan to San Fernando, Pamgpanga. The march lasted from five to nine days.

Approximately 80% of the prisoners were Filipino nationals.

Now known as the Bataan Death March, many soldiers, already malarial and exhausted, were not given food or water; several were physically abused and beaten along the trail. Those who could not continue were executed. Many others died in captivity. The living became slave laborers.

At San Fernando, the prisoners were placed into train cars made for cargo and railed to Capas, Tarlac, a distance of 24 miles. Many died standing up in the railroad cars, as the cars were so cramped there was no room for the dead to fall.

They were then marched another six miles to their final destination, Camp O’Donnell, where additional atrocities against the soldiers occurred on a regular basis.

In response to the Japanese occupation, a Filipino guerrilla army sprung up, and in 1944, they joined forces with U.S. troops under General Douglas McArthur.

The Filipino guerrillas were inducted into and became official members of the Army. They began offensive liberation efforts in October 1944, which culminated in the Allied victory in the summer of 1945.

The 1946 Rescission Act: The Other Truman Doctrine

After the war ended, President Truman signed two laws – which together are called the 1946 Rescission Act – which annulled the U.S. offers of citizenship and veteran benefits to Filipino World War II veterans and recognized Filipino guerrilla units.

Of the 66 countries allied with the U.S. during World War II, only Filipinos were denied military benefits.

Before the rescission went into effect, only 4,000 Filipino veterans who had survived were able to obtain U.S. citizenship.

Efforts to rectify the effects of the Rescission Act of 1946 are ongoing. 70 years later, the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Policy is part of this legacy.

The Immigration Act Of 1990

Some progress was made 45 years after the war ended, when George H.W. Bush signed the Immigration Act of 1990 into law, granting an offer of citizenship to Filipino World War II veterans.

By then, the number of eligible Pinoy veterans had greatly dwindled.

Over 50% of those who enlisted to serve the United States in World War II had died during the hostilities.

In the intervening 45 years since the Truman rescission, thousands of would-be eligible Filipino veterans had passed away.

In the end, only 26,000 Filipinos were granted U.S. citizenship under the 1990 Act.

Despite the reduced pool of eligible beneficiaries, the 1990 law did not include any benefits, such as medical care and senior pensions, for the veterans. As a result, many who applied for citizenship – already in their 60s and 70s – ended up living on social security.

Adding insult to injury, opposition to the naturalization measure was quixotically led by the Department of Veteran Affairs, which openly worried the new law would create benefit and pension entitlements for those who qualified for citizenship.

Worse, the good news begat a fresh set of problems.

Family separation and reunification.

Whereas the door to live in the U.S. as citizens was finally opened for the World War II veterans, the pathway excluded many of their children.

Even though the veterans could apply for naturalization, their oldest offspring were not allowed to join them in the United States.

Since so much time had elapsed, the vast majority of the veterans’ children were now adults, over 21. This placed them in lower categories of the family preference visa system.

For Filipinos, a 20+ year wait for a visa to become available to an adult child, married, is not uncommon.

As explained in Renewing The Battle For Family Unity, there is a numerical cap on green cards issued annually based on family relationships. No more than 7% are allotted to a country.

These limits clog the system for individuals from countries with higher rates of immigration applications.

The Philippines, along with Mexico, have the longest waiting time in the adult child categories.

Attempts to ease restrictions for the adult children of Filipino veterans fell on deaf ears.

Filipino Veterans Equity

Compensation Act Of 2009

In 2009, the Filipino Veterans Equity Compensation Act was enacted.

Under this bill, Filipino World War II veterans, who had become U.S. citizens, were granted a one time payment of $15,000.

Non-citizen Filipino veterans were granted a one-time payment of $9,000.

Filipino-American activists asserted, under the original promise, Filipino World War II veterans should have received the same monthly pension that other veterans get, and not merely a one-time lump sum payment.

Additionally, the funds were only made available to living veterans – not to their spouses or other survivors.

Approximately 43,000 claims were filed to obtain the one-time payments. Only 18,000 were approved.

Some were denied because veterans missed the September 2010 filing deadline.

Others failed because the guerrilla rosters compiled by the Army during the war were rejected as lacking complete identity identification – even though various Army officials testified at Congressional hearings that they had “complete confidence” in the 1942 – 1948 records of Filipino military service.

Various law suits filed by Filipino veterans are still pending. Several veterans have said the $15,000 is symbolic, and not as important as winning their honor and justice.

Filipino family separation and reunification were again ignored.

Kinks In The Filipino World War II

Veterans Parole Program

Given the ongoing absence of Congressional action on matters of immigration, President Obama once again used his executive authority to establish the newly-announced parole policy for Filipino veterans.

The action was spurred by a report, Modernizing and Streamlining Our Legal Immigration System, issued in July 2015.

In short, the program will enable certain family members of Filipino World War II veterans with approved visa petitions to await for their priority dates – the invisible ticket dates for green card applications to become current.

For aging veterans and their spouses, the benefit is obvious. Their young family members can live in the U.S. on a temporary basis and provide care, comfort, and support for their elderly relatives, while awaiting their permanent residency interviews.

However, the parole program fine print warrants caution, as usual with immigration policies.

ADMINISTRATIVE CONCERNS

Procedural and processing quirks are bound to arise.

For instance:

- Applicants need to be aware that approval will not be automatic. And as often happens with new immigration programs, applications run into problems due to unforeseen circumstances in individual situations.

- Since decisions are made on a discretionary basis, differences in interpretation of who qualifies may differ from adjudicator to adjudicator.

- Training of USCIS staff is another concern. In the beginning, it should be anticipated Filipino family unity parole applications will likely be processed slowly.

There are four basic requirements for the Filipino Veterans Parole Program:

- The family relatives must have an approved I-130 family based petition already approved

- The sponsoring relative must be a Filipino World War II veteran or surviving spouse

- The veteran (or surviving spouse) must reside in the United States

- The family relative must still be waiting for his or her immigrant visa priority date

Parole vs Visa

The Filipino World War II Veterans program is a parole, not a visa, program. This means, like a visa, Filipino family members will be allowed to enter the U.S. legally. But it does not grant them a green card or permanent resident status.

What If The Veteran Is Deceased?

Under the rules for humanitarian reinstatement, the surviving spouse can apply for the parole of the adult children.What If The Veteran Moved Back To The Philippines?

Since the goal of the program is to allow Filipino children to join their parents in the U.S., unless the veteran returns to live in the United States, it seems the children would not qualify.

FILIPINO OVERSTAYS

Based on my experience as a family immigration attorney for Filipinos, one issue that seems likely to arise pertains to individuals who entered the U.S. legally on a visitor or student visa several years ago, but stayed with their elderly parents, rather than return back to the Philippines when their visas expired.

To qualify for parole status, they would need to return to the Philippines to process their parole application. However, upon departing the U.S. they trigger the 3 to 10-year bars to admissibility.

In such cases, these individuals might be better served by waiting, however long, for their priority dates to become current and attend their adjustment of status interviews here. During the interim period, they remain vulnerable to immigration arrest and detention, and being placed in deportation proceedings at immigration court.

FIVE YEAR PERIOD OF OPPORTUNITY . . . OR LESS?

Unfortunately, the duration of the president’s executive order is unclear.

USCIS representatives have pointed out that FWVP applicants have five years to apply for parole under the FWVP. At that point, the government will review the program to determine whether an extension will be necessary.

However, the president’s directive may no longer apply once he ends his term of office in January 2017. His successor could decide to discard the program.

Too Little, Too Late Yet Better Than Never

70 years ago, then President Harry Truman broke a promise to Filipinos who had fought side-by-side with American troops in defeating Japan during World War II.

Like the resolve they mustered, even while in captivity, to overcome their adversaries, Filipino veterans have continued to battle to restore the commitments made to them in 1941.

Last week, their determination led to the creation of the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program.

One such veteran, Rudolpho Panaglima, has been waiting for that moment for decades. He was 13 when he joined his father in a Filipino guerrilla unit that was coordinating with U.S. forces. Being so young, he was able to sneak past the Japanese military as a courier and scout.

This National Public Radio broadcast recently shared his story.

In my view as a San Bernardino immigration attorney, while the current parole policy is commendable, it pales when compared to the scope of the promises broken by Truman 70 years ago.

According to USCIS estimates, approximately 2,000 to 6,000 Filipino-American World War II veterans live in the U.S. today. This is a far cry from the pool of 260,000 Filipino World War II enlistees.

The higher figure – 6,000 – means less than 2.5% of Filipinos who ventured into war for the U.S. will experience a small semblance of the original promise made to them.

Under the lower estimate, less than 1%.

Bluntly stated, both statistics are disgraceful.

Pinoy veterans like Panaglima should not have endured citizenship-related obstacles from the U.S. for a job well done.

Nonetheless, those who continued to fight for naturalization and full benefits, as promised, have honored and paid tribute to all the thousands of Filipinos who enlisted to fight for the United States during World War II.

It’s time for the U.S. to go a step further. Parole is not enough.

At minimum, a direct path to permanent residency should be built for the children and spouses of living Filipino World War II veterans or their surviving spouses who eventually became U.S. citizens.

Political reciprocity demands nothing less – especially for aging individuals who put their lives on the line for the U.S. when they were in their prime years of life.

Besides, as demonstrated by Filipino veterans during World War II, good friends help those in need.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics

If you’re serious about figuring out if the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program can bring or keep your family members together . . .

Let’s schedule your Strategy And Planning Session today.