Despite Congressional smiles when cameras are turned on, a meeting of political minds on the contours of immigration reform may not take place anytime soon.

In the meantime, most elected officials agree on at least one issue. Immigrants who seek lawful status must “get in the back of the line”.

Unfortunately, colorful political rhetoric often does not reflect legal realities.

And it’s not a solution.

The Political Myth Of One Immigration Line

First things first, there is no one immigration line for would-be permanent residents. As a green card lawyer, I can personally attest there are several immigration lines.

Second, in legal jargon, what politicians refer to as immigration “lines” are called immigration “categories” in the legal world.

To understand how these lines really work, we need to descend down a confusing rabbit hole of processing green card applications.

At the outset of this journey, it’s important to recognize two distinct routes exist for pursuing legal residency in the United States. The first pertains to family relationships. The second rests on employer sponsored petitions.

In this article, I focus on family-based applications.

Each family-based line has different waiting times, due to three factors:

- (1) The category, or type, of green card sought by an immigrant.

- (2) The immigrant’s country of origin.

- (3) The number of available visas for the immigrant’s category and country of origin.

As I will show below, those who are most vulnerable to the “back of the line” rhetoric are already subject to the longest waiting times.

First stop: How does an immigrant get in line?

The Priority Date: Your Invisible Ticket For Getting In Line

The green card process begins with the filing of a relative petition, on behalf of the immigrant, by a family member.

If the petition is approved, the immigrant is given a priority date.

The priority date operates like a “place in line” ticket given to a person visiting Verizon to buy a new cell phone. When a company representative is available to assist you, your ticket number is called.

However, immigration authorities will not directly notify you that your waiting period is over.

Instead, at the beginning of each month, the government issues a visa bulletin informing the public about the most current number, or priority date, they are working on.

In essence, the priority date serves as an invisible ticket for an invisible line.

This means our green card system is based on a first come, first served process. Contrary to political talk, new immigrants are always sent to the back of the line.

Government officials use the phrase “Your priority date is current” to indicate the waiting period is over. At this point, an immigrant can finally go to step two in the green card process and file an application for permanent residence.

Some immigrants living in the U.S. are interviewed at local offices. This is called adjustment of status.

Others are living abroad and attend interviews in their home countries. This is known as consular processing.

Several more reside in the U.S. but are required to return their home country for their green card interviews. Many individuals in this situation will also need to file for a non-guaranteed I-601 hardship waiver to ensure their rights to live in the United States.

Second stop: Which line does an immigrant get in?

The Family Preference System: Green Card Lines For Immigrants

The rules governing an immigrant’s category and country of birth were set forth by the Immigration Act of 1965.

The Act divided family-based applications into two major categories.

Immigrants in the first category are classified as “immediate relatives.” This category includes the spouses, minor children (unmarried and under 21), and parents of U.S. citizens.

There are no quotas on the number of green cards which can be issued to immigrants classifiable as immediate relatives.

Immigrants in the second category fall under the family preference visa quota system. (This is the group of immigrants referenced by the current political “get to the back of the line” grandstanding.)

Family preference immigrants are sub-categorized into distinct lines:

- First Preference: Unmarried children, over 21, of U.S. citizens

- Second (2A) Preference: Spouses and unmarried children, under 21, of lawful permanent residents

- Second (2B) Preference: Unmarried children, over 21, of lawful permanent residents

- Third Preference: Married children of U.S. citizens

- Fourth Preference: Brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens

Unlike immediate relatives, there are annual limits on the number of immigrants who can receive immigrant visas, and hence green cards, via the preference system.

Due to these limits, they must wait a longer period of time before they are eligible for file their permanent resident applications and their interviews are scheduled.

Third stop: How long does each line take?

Longer Lines, Longer Delays Are Not The Solution

It is not unusual for the immigration family visa preference process to take 10 to 20 years before a visa becomes available.

According to Suzy Khimm, a reporter for the Washington Post, the wait can take up to 24 years.

She’s right.

As a San Bernardino immigration attorney, I’ve heard tragic stories where the sponsored relatives died more than 20 years after their petitions were filed, still dreaming of the day when their priority dates would be current.

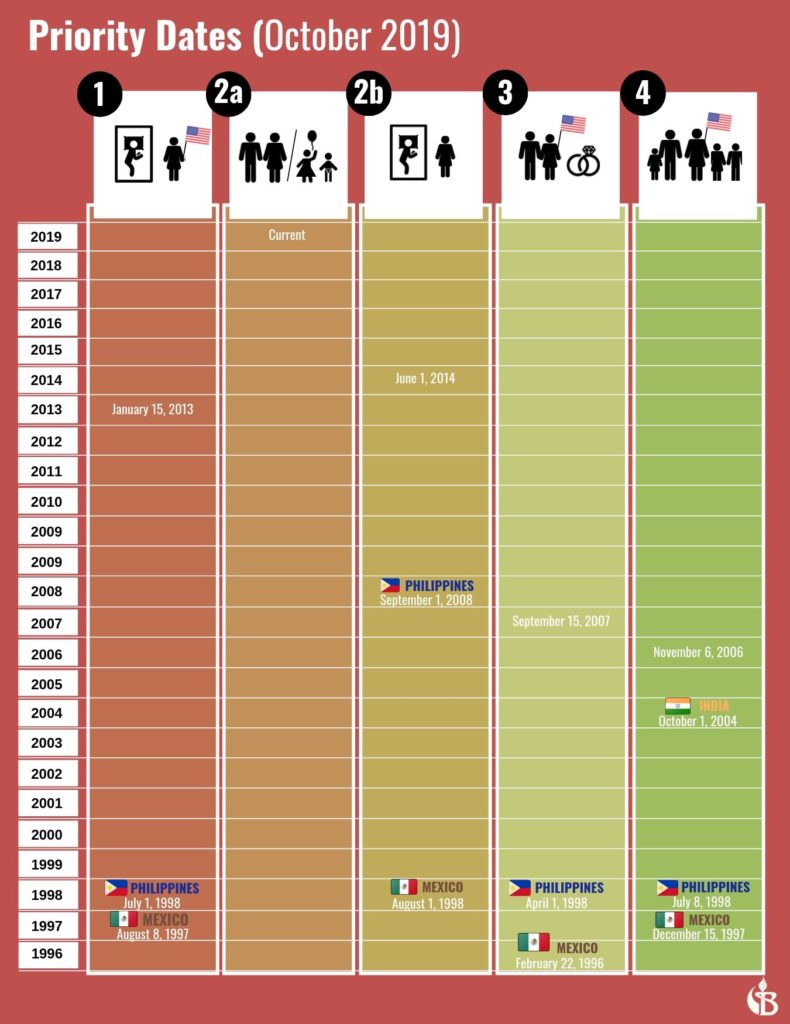

The following diagram, taken from the October 2019 Visa Bulletin, is instructive:

As explained earlier, how long an immigrant must wait for an available visa depends on the immigrant’s family preferences category, country of birth, and the number of available visas for the immigrant’s category and country of origin.

Over time, due in large part to outdated country quotas, our current system has led to a huge backlog of immigrants, waiting to reunite with their family members, in all family preference categories.

How Long Is Your Immigration Line?

For instance, using the above diagram, take the 2b category.

For most countries, the government was processing applications for unmarried sons and daughters with a priority date of June 1, 2014.

But if the application belonged to an immigrant from the Philippines, they were working on papers filed on or before September 1, 2008.

For Mexican immigrants, the government was still handling applications filed by August 1, 1998.

Since this example is based on an October 2019 visa chart, this means the government was backlogged about 5 1/2 years for most immigrants, 11 years for Filipino immigrants, and 21 years for Mexican immigrants in the 2b category.

The processing of green cards is not an model of efficiency.

Sadly, this example is true month after month.

This backlog, of course, has its greatest impact on countries with stronger migration flows to the United States – Mexico, the Philippines, and in certain categories, China and India.

The connection between these long lines and the amount of undocumented immigrants seems obvious.

The lengthy delays induce many immigrant families to despair. Some living outside the United States resort to entering without permission, instead of waiting countless years for a visa to become current.

In addition, nearly 50% of the 11 million immigrants living in the U.S. without proper authorization are already standing in line, trapped in the backlog of preference category applications.

Nonetheless, politicians at the front of the immigration debate continue to assert successful reform requires sending undocumented immigrants to the back of the immigration line.

Do they not understand the realities of green processing realities? Such ignorance does not bode well for the success of immigration reform.

Or worse, are they merely using get-tough soundbites to fool a public not versed in immigration law?

Either way, the proposed cure is ill-suited for our broken immigration system.

Longer lines, longer waits will increase, not decrease, the amount of undocumented immigrants.

This is not to imply that immigrants who enter without government inspection should be accommodated.

Rather, to the extent such behavior is prompted by an outdated process of allocating visas, modification of distribution regulations is a rational course of action.

Fixing our dilipated immigration structure requires a thoughtful multi-faceted approach that addresses immigrant family categories, priority dates, and waiting times.

In other words, the government needs to repair and revitalize our family unity system at its roots.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics